Preparing vegetable boxes at Growing Communities, a local food social enterprise in Hackney.

Context

Your ENERGY DESCENT ACTION PLAN (5.1) (if you do one) will identify a range of key catalysts for the creation of STRATEGIC LOCAL INFRASTRUCTURE (5.5), and will stimulate thinking about SCALING UP (5.3) your initiative to take a greater role in making that happen. Also, as a range of PRACTICAL MANIFESTATIONS (3.9) start to emerge, and the need for FINANCING YOUR WORK (3.3) in the current funding-starved environment, it makes sense to start looking WORKING WITH LOCAL BUSINESSES (3.12) and also to thinking about what new enterprises can be created from what your initiative is doing.

(We are collecting and discussing these Transition ingredients on Transition Network’s website to keep all comments in one place. Please leave feedback and comments, suggestions for alternative pictures, anecdotes, stories and projects for this ingredient here).

The Challenge

The model of community initiatives that are dependent on external funding from philanthropic organisations, governments and external grant giving bodies is becoming increasingly redundant as economies contract and budgets shrink. In a wider context, we are still living off the surplus generated at a time of high Energy Return on Investment, which enabled surplus to be redistributed. That window of opportunity is starting to close as we enter a time of declining net energy and economic contraction. There is often a resistance within community organisations, especially those with an environmental agenda, to think about how they might operate in such a way that pursues their ethics but also functions as an enterprise, generating revenue for the ongoing development of the organisation, but that resistance needs, increasingly, to be overcome.

Core Text

As your Transition initiative evolves, it will need to make some choices about how it evolves. There is one model, more common among environmental organisation, which is for it to continue as a largely volunteer-driven effort, dependent on occasional grants and income from events, but this is an approach which comes with certain risks. As Middlemiss and Parrish put it[1], “volunteers can face challenges in running grassroots initiatives for sustainability, including hostility from local people, difficulties in securing funding, and ‘burnout’ as the strain of volunteering with limited support takes its toll”. Also, if the aim in the longer term of Transition is the creating of a new, economically viable local infrastructure which in turn creates livelihoods, skills and resilience, these projects need to be economically viable.

The concept of social enterprise is something that is gaining a lot of traction and interest at the moment, not least from the government with its ‘Big Society’ agenda, but what does it actually mean? The first thing to note is that it is really not a new idea at all. The Cooperative movement in the 1860s created viable businesses which were built around the need to strengthen local economies and create meaningful employment and local ownership. Future Builders define a social enterprise as “a business or service with primarily social objectives whose surpluses are principally reinvested for that purpose in the community, rather than being driven by the need to maximise profit for shareholders and owners”[2].

In essence, they are financially viable enterprises, with explicit social aims, and with a model of ownership which increases social participation. Often they are the product of one visionary, bold individual with a big idea, an entrepreneur. As the Skoll Foundation put it, “social entrepreneurs act as the change agents for society”[3]. I asked Nick Temple of the School for Social Entrepreneurs[4] what were the qualities of a social entrepreneur. He told me that being a social entrepreneur is as much a mindset and an attitude as a specific business model, and that in essence it is about approaching social and environmental problems with an entrepreneurial mindset. I asked him if he had 4 tips for individuals or projects within a Transition group wanting to develop a social enterprise. Here they are:

1. Just get on and do stuff: the best thing is to get started and to learn from your own and other people’s experience. Pilot things, measure what happens, don’t wait for permission, just get started on a scale which feels achievable

2. Mission before everything else: why are you doing this? What is the big idea? Being clear about your mission enables you to check back against it when you are planning how your enterprise will function … everything else flows from a clear mission

3. Measurement: the whole reason for creating a social enterprise, as opposed to a more conventional business model, is to make a difference, to make things happen, to produce beneficial impacts. Measuring the impacts you are having is vital in terms of funding, investment, credibility and so on. A range of tools already exist for measuring social impact, don’t reinvent the wheel.

4. The Person is the Organisation: social entrepreneurs often have a certain ‘something’. They don’t go to an interview for what they do, in that respect they are self-appointed, but they have often got to where they are through being naturally gifted at building trusted relationships and leading by example.

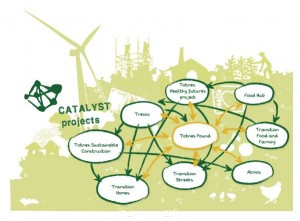

As a result of its Energy Descent Action Plan process[5], Transition Town Totnes identified a number of what it saw as ‘Catalyst Projects’, things it saw as being central to the relocalisation process, which could be viable social enterprises, and which could interconnect in some interesting ways (see left). But what might it look like if a Transition initiative tries to create a culture of social entrepreneurship in order to develop enterprises like this? This is still an area which is emergent, but here are a few thoughts.

As a result of its Energy Descent Action Plan process[5], Transition Town Totnes identified a number of what it saw as ‘Catalyst Projects’, things it saw as being central to the relocalisation process, which could be viable social enterprises, and which could interconnect in some interesting ways (see left). But what might it look like if a Transition initiative tries to create a culture of social entrepreneurship in order to develop enterprises like this? This is still an area which is emergent, but here are a few thoughts.

Often in the environmental/activist world there is a resistance to the idea of bringing business thinking to activism, the two cultures don’t necessarily sit easily alongside each other. However, as Nick Temple of SSE puts it, “the important point is to not fear business, not all successful businesses are inherently in some way wicked. All of the practices utilised by business aren’t evil, they have evolved over time with good reason”. At the end of the day, if an operation doesn’t make money, it loses money, and that has to come from somewhere. When you start looking at the potential and the possibilities created through a process of intentional localisation and resilience-building, the number of potential new enterprises is huge.

So what would it look like if your Transition initiative set out to found itself on a culture of social enterprise, and to look to create a new generation of entrepreneurs dedicated to making localisation happen? Firstly, inspire people with some good examples of existing social enterprises, arrange visits, bring in inspiring speakers. You might then offer some kind of training, ideally drawing in local entrepreneurs, and provide an engaging course perhaps spread over a few evenings. You might also invite some input from the School for Social Entrepreneurs, UnLtd, or any local organisations with relevant skills. If you have identified particular catalyst projects, there are organisations who offer some start up resource in order to take the project up to a stage of being investment ready, for example the National Energy Foundation[6] for energy projects or the Community Builders Programme[7]. The skills and support are available, all that is required is a refocusing of the vehicle by which the initiative plans to move forward.

The Solution

The relocalisation process creates huge potential for a range of industries, energy companies, local food businesses, manufacturing and so on, which could either be run purely for profit, or in such a way that they are commercially viable and also reinvest their surplus into the wider community. Understand, from an early stage, the need for social entrepreneurship, and design and support emergent initiatives. Provide training and events, and link with existing providers of support for entrepreneurship.

Connections to Other Patterns

Successfully creating a culture of social entrepreneurship, both within your initiative and within the wider community will depend, in part, on successfully BUILDING STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIPS (2.12). While each enterprise will be different and will develop its own approach, there is much that can be drawn on to avoid reinventing the wheel. For example, there is much that can be learnt from the COMMUNITY OWNERSHIP OF ASSETS (5.8), the movement around COMMUNITY SUPPORTED AGRICULTURE/FARMS/BAKERIES (5.9) and approaches for ENSURING LAND ACCESS (3.13). Other tools that may be useful include ENERGY RESILIENCE ASSESSMENTs (4.5) as a way of ensuring you build in resilience from the start, and also the need for ongoing MEASUREMENT (2.5).

Organisations that can offer support

• The School for Social Entrepreneurs: www.sse.org.uk

• Regional Social Enterprise bodies; eg. Social Enterprise London (www.sel.org.uk)

• Social Enterprise Coalition: www.socialenterprise.org.uk

• UnLtd: www.unltd.org.uk

• www.socialenterpriseambassadors.org.uk

Further Reading

Baderman, J. & Law, J. (2006) Everyday Legends: the stories of 20 great UK Social Entrepreneurs . WW Publishing.

Crutchfield, L, McLeod Grant, H. (2007) Forces for Good.

Dearden Phillips, C. (2008) Your Chance to Change the World: the No-Fibbing Guide to Social Entrepreneurship. DSC.

Dees, G. (1998) The Meaning of Social Entrepreneurship. Duke University.

Elkington, J. & Hartigan, P. (2008) The Power of Unreasonable People. HBS.

Leadbeater, C. (1997)The Rise of the Social Entrepreneur. Demos.

Mawson, A. (2008) The Social Entrepreneur. Atlantic Books.

Nicholls, A. (2008) Social Entrepreneurship: new models of sustainable change. Oxford University Press.

Young, C, Edwards-Stuart, F. (2007) Leadership in the Social Economy. School for Social Entrepreneurs.

[2] http://www.futurebuilders-england.org.uk/making-sense-of-futurebuilders-terminology/

[3] Skoll Foundation (2009) Glossary of Terms Used in Application Materials. http://www.skollfoundation.org/skollawards/glossary.asp

[4] http://www.sse.org.uk/

[5] Hodgson, J, Hopkins, R. (2010) Transition in Action: Totnes and District 2030: an Energy Descent Plan. Transition Town Totnes/Green Books.

[6] http://www.nef.org.uk/

[7] http://www.communitybuildersfund.org.uk/

Please leave any comments here.

Many of you who attended or followed the 2010 Transition Network conference will have either been to, or have subsequently

Many of you who attended or followed the 2010 Transition Network conference will have either been to, or have subsequently